Past Featured Objects

Simon Willard’s Chair

American Federal Hepplewhite mahogany Martha Washington or Lolling chair, c.1800, likely Massachusetts. The frame includes wooden scrolled arms, tapered squared legs with the original connecting stretchers, and blocked front feet. The piece was reupholstered in an ornamental pale yellow with round brass upholstery nail trim.

Bequest of Mary Cowell

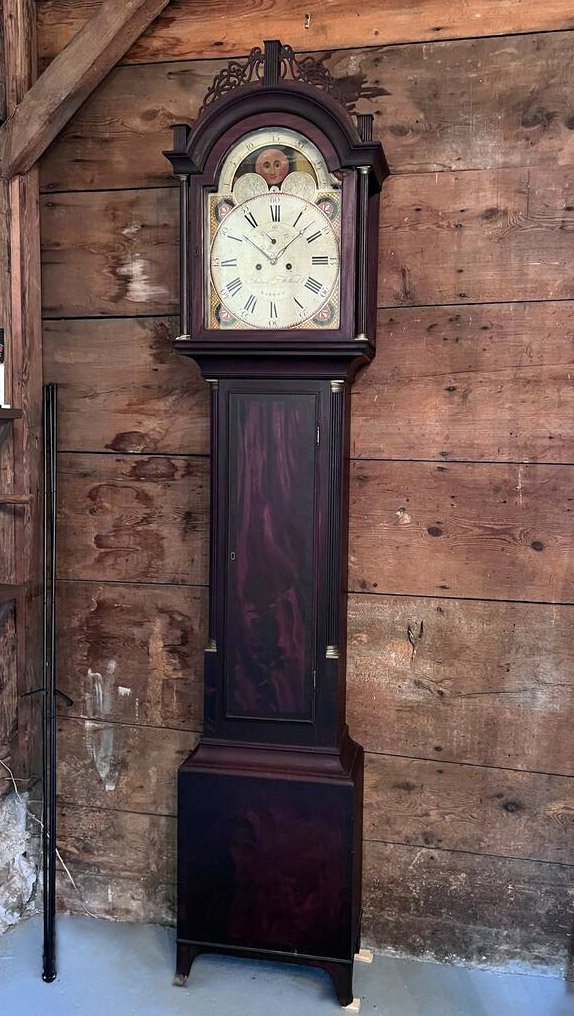

Eight-day musical clock by Simon Willard (1757-1844), Roxbury, c. 1793

Made for Samuel Bass (1757-1842) of Roxbury, this eight-day clock measures an impressive 107” tall. The mahogany case has been attributed to Stephen Badlam (1751-1815), notable Dorchester cabinetmaker. The dial is signed by John Minott (1771-1826), the subject of our featured “featured book” below.

Early American clocks are a rarity due to how complex and time consuming they were to create. That translated to a much larger price point, anywhere from two to three times the price of a standard tall clock. They usually played six or seven tunes on average; this having seven: 149th Psalm (for Sundays), Buttered Peas (what it is currently set to), British Grenadiers, The Marquis of Granby, Lady Coventry’s Minuet, Nancy Dawson, and Bold Highland Laddie.

Edwin Wesson (1811-1849), hunting rifle, c.1835, 46" x 6.5" x 1.75".

Edwin Wesson made hunting, target, and sporting percussion rifles and pistols in North Grafton from 1734 to 1740 at which point he moved to Northboro, MA. He died at the height of his success. His most notable work included innovations in cylinder and barrel design, making his firearms not only more reliable but also more accurate. Daniel Wesson, his brother whom he trained, continued the gunsmithing business finding great success after partnering with Horace Smith.

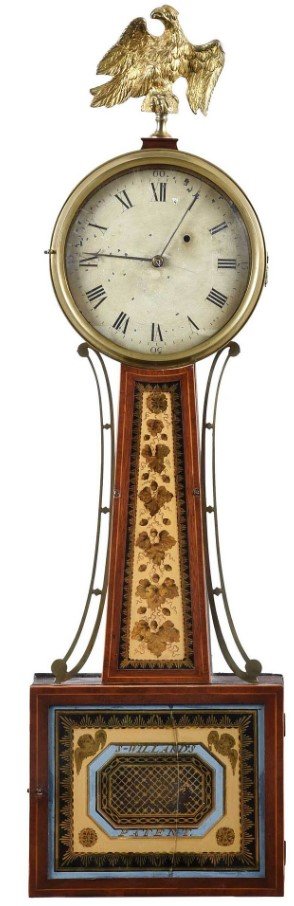

Aaron Willard Jr. (1783-1864), figure-eight wall regulator, 1830-1835. 50.5” x 15.25” x 6.5”.

A large variation on Simon Willard’s patent timepiece form, likely used in a business. The use of “regulator” in its name indicates a deadbeat escapement, and therefore more accurate timekeeping.

This piece is part of the Charles Grichar Collection, but has been displayed in Willard House since its purchase at auction.

Original by John Ritto Penniman (1782-1841), c. 1799

Oil on canvas.

29 x 37 in.

Art Institute of Chicago

Willard House owns an enlarged photographic version of this painting as an educational aid. This is the Roxbury which our clockmakers, their journeymen/apprentices, and fellow artisans knew. Their workshops are not pictured in this view; this is the church and the wealthier residents of Roxbury. This does show the church they all attended, the green where their livestock could graze, and some of their clients, major factors in their lives.

The view also ties to one of our more important objects, the gallery clock from the First Church of Roxbury, which hangs on the wall opposite.

Simon Willard Jr. (1795-1874), Boston, c. 1840

These precision timepieces were made initially for astronomical purposes such as observing the transits of Mercury and Venus and therefore were originally found in observatories. Most of these observatories were not large professional public structures as we would imagine. They were often built by individuals with the interest and the capital to follow that interest.

These pieces were useful for non-astronomical purposes too. They were used to keep other clocks accurate, and later to keep train schedules accident free.

This example is part of the Grichar Collection and features a Greek column inspired case.

Patent Timepiece

Simon Willard (1753-1848), Roxbury, 1803

It is rare that we have an exact date for a piece, and we do not always know who painted the glasses. This recent acquisition was signed “John R. Penniman/Boston 1803”. John Ritto Penniman (1782-1841) was an ornamental artist who did work for Simon and Aaron Willard among others. He is represented several times in the museum regarding portraits and scenic paintings, but not on any of our timepieces until now.

Aaron Willard Jr. (1783-1864), Boston, 1812-1815

This recently acquired piece features a Roxbury style mahogany/mahogany veneer case likely made by Thomas Seymour (1771-1847). The painted iron dial is attributed to to ornamental artists Nolen (1784-1849) and Curtis (1785-1876) with original signature penned by Spencer Nolen.

The dial states "Aaron Willard Jr., London" which is unusual since neither Aaron Willard ever worked in London. Upon further inspection, one can see the shadows of the "B", "S", and "T" under the "L", "N", and "D" meaning the location was altered at some point. Why? This clock belonged to a to a Virginia family. The "Boston" was likely replaced with "London" during the Civil War to erase any connection with the North.

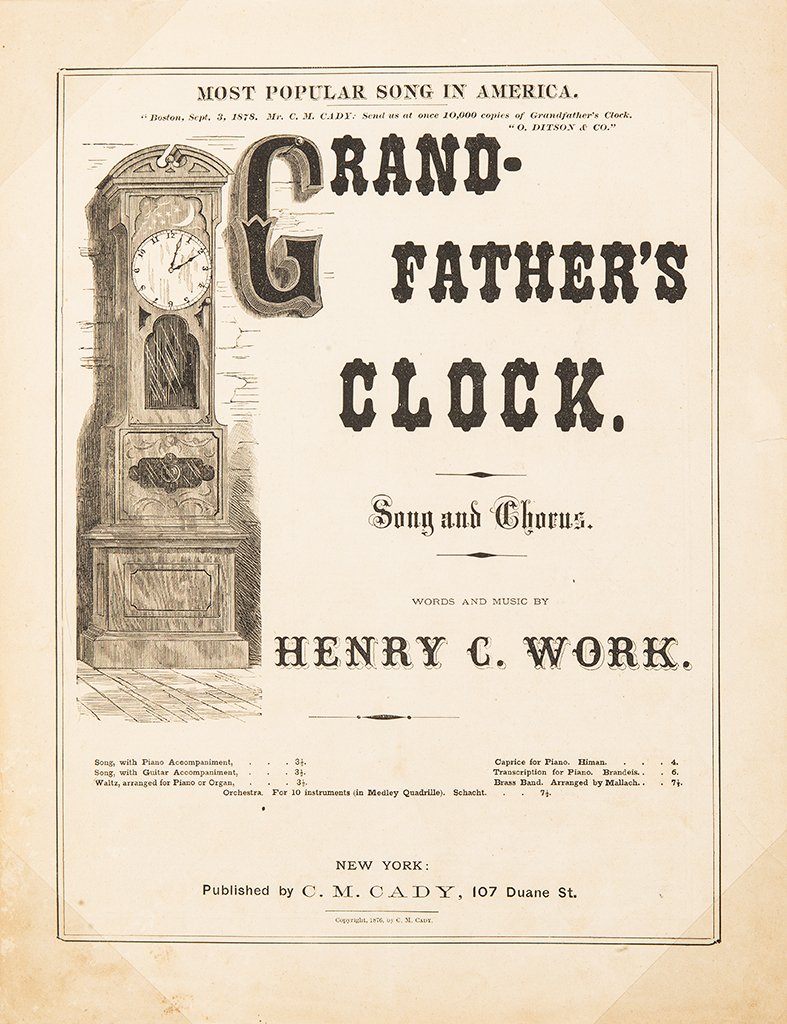

Henry Clay Work (1832-1884), sheet music My Grandfather’s Clock, 1876. This work became so popular that it influenced nomenclature which continues today. Previously these clocks were called tall case, longcase, or 8-day. This song created the term “grandfather clock.”

Lewis (1779-1814) and Alpheus (1785-1842) Babcock piano, Boston, MA c.1810. Lewis apprenticed under the first Massachusetts pianomaker, Benjamin Crehore (1765-1831). He and his brother, Alpheus, then opened their own shop at 49 1/2 Newbury Street, Boston in 1810. By 1812 they were partnered with organ builder Thomas Appleton (1785-1872). This piece is therefore an early example of the Babcock brothers’ work as well as a beautiful addition to our gallery!

Simon Willard’s eyeglasses c.1800. These are most likely magnifiers to correct presbyopia or farsighted vision as a result of age. These came from the estate of Simon’s great great granddaughter, Mary (Monks) Cowell.

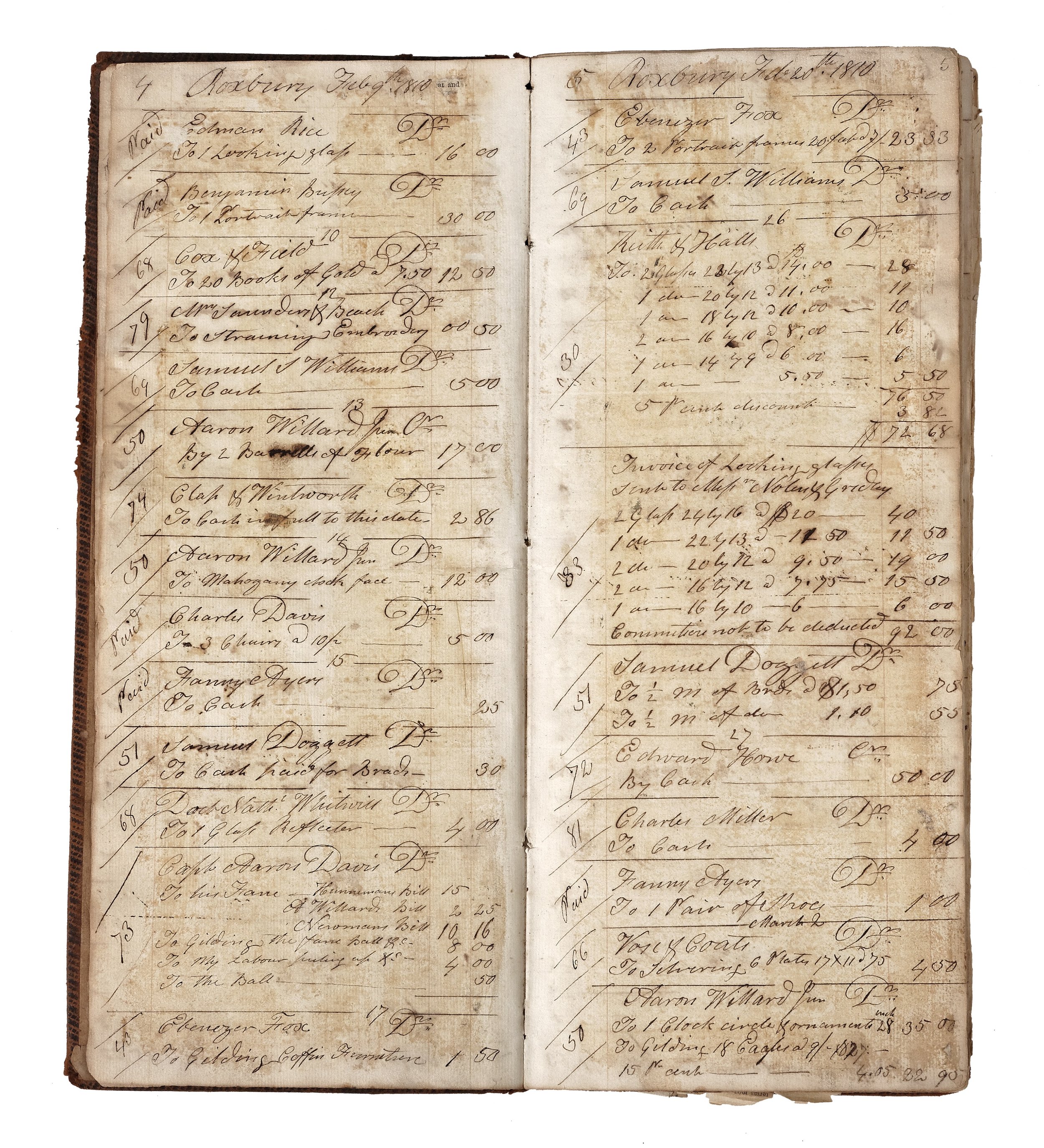

Two pages from 1810-12 John Doggett (1780-1857) Daybook. Daybooks were financial documents that recorded the debits and credits that occurred in a business from day to day. Documents like this and bills of sale are very important when researching objects and piecing together an artists life. It is through the daybooks of other artisans who worked with the Willards that we have insights into their business.

Glass from a c.1815 Aaron Willard Jr. (1783-1864) Willard Patent Timepiece. Early patent timepieces glasses had a more geometric/architectural look, but began to become more intricate and scenic. Here we have a wonderful example depicting the then recent War of 1812. This exact scenario likely never happened, but represents two major occurrences during the war.

Spencer Nolen (1784-1849) was a Boston area ornamental artist. In 1808 he married Aaron Willard’s daughter Nancy; they likely met through his work with her father. Willard House has an example of both his dial painting (above) and reverse glass painting (below).

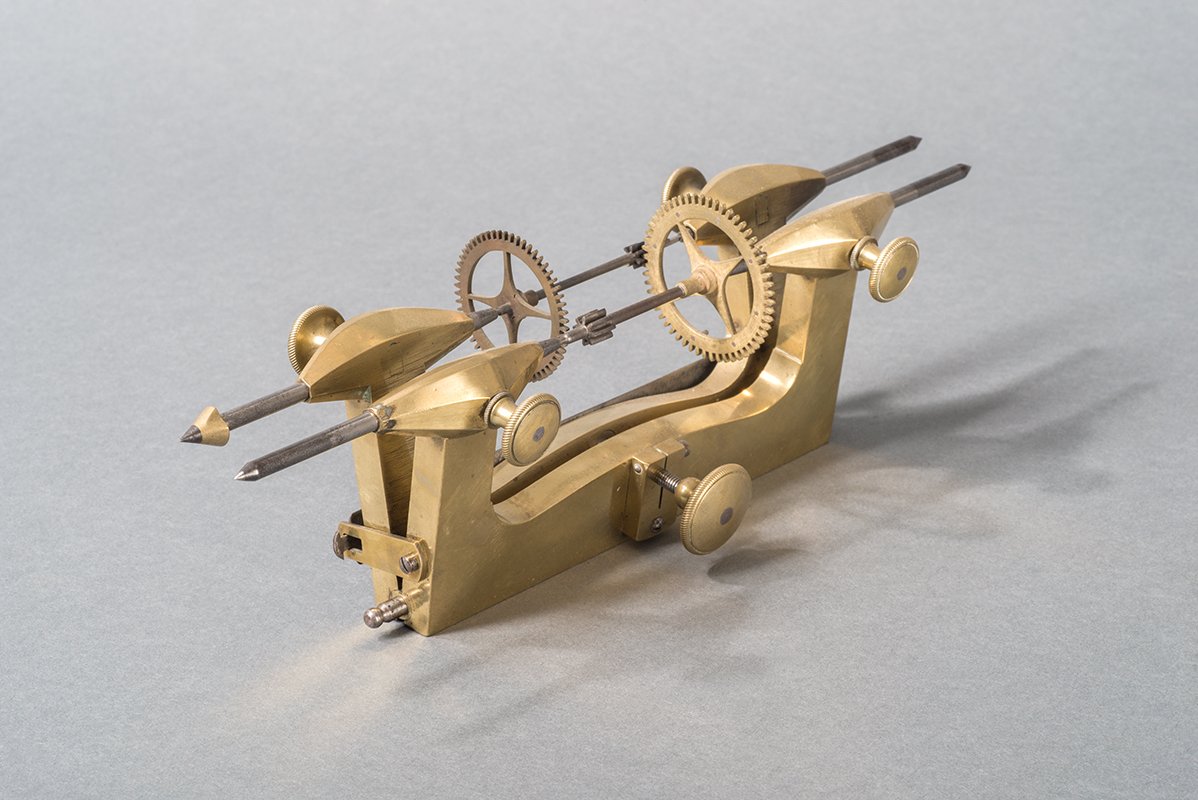

Brass and Steel Depthing Tool, with steel runners and hatched thumbscrew tighteners, the balance is supported by one of its own pivots, while the one being worked on is resting on one of the grooved spindles.The adjustable u-shaped base supports the runners which are aligned to hold the wheels and arbors, all tightened with thumbscrews.

Brass, signed "E.Taber $11.00 May 4 1839" may have been bought from Simon Willard.

Aaron Willard (1757-1844), Roxbury, Massachusetts, Eight-day rocking ship clock (c.1790)

The clock arch displays a ship at harbor rocking in the waves. This effect is achieved by extending up from the pendulum and attaching a ship painted on tin. The strike weight contains a door to adjust the weight or hide valuables.

Patent Alarm Timepiece by Simon Willard (1753-1848) made c.1824 for Mr. George Tilly Rice. This piece descended through his family until 2014 when it was donated to Willard House by his great-great granddaughter.

George Tilly Rice (1796-1867) was a Worcester banker, sponsor of the Blackstone Canal, member of the Fire Society, and founder of the Nashua & Worcester Railroad. This piece was likely commemorative of either his work with the canal or the Fire Society.

Minott was a pioneering painter of tall clock dials working primarily for the Roxbury/Boston, MA Willard clockmakers in the late 18th century. Dozens of his signed tall clock dials have been identified, documented, and are illustrated in this new work.

The author traces Minott’s relatively melancholy career that brought him great financial success followed by economic and personal failure at the time of the near collapse of the New England economy during the War of 1812.

Backsaw owned by Benjamin F. Willard (1803-1847), son of Simon Willard (1753-1848). Metal body with golden color top rail and carved handle. Marks include Benjamin's name and the year 1820.

Boston painted eight-day clock dial, circa 1795 with distinctive printed “Aaron Willard”

signature, floral decorated corners with raised gilt gesso borders, transfer printed “half map”

hemispheres, and moon’s age dial in the arch showing the new moon position. This dial can be

attributed to Boston ornamental artist John Minott (1772-1826).

Benjamin Willard (1743-1803), Grafton, Massachusetts, Eight-day Clock, c. 1770

With later case made by David Young, Hopkington, NH, c. 1800

Carving done late in the 19th century

Owned by the Bill Family of Paxton, Massachusetts in the 19th century. It accompanied one member of the family in dormitory living first at Worcester Academy, then to Amherst College and finally to Harvard Law School. Despite its altered condition, this clock deserves a place in this museum for the interesting family history it carries with it through the centuries. It is no doubt the most ‘educated’ clock in the collection!

Aaron Willard (1757-1844) Eight-day clock

Stephen Badlam (1751–1815) constructed this case for Aaron Willard (1757–1844). Primary wood, mahogany.

The painted lunar calendar ("moon-phase" dial) on the dial features a seascape and a landscape (shown in the detail to the right).

Simon Willard (1753-1848) 30-hour Timepiece with Passing Strike and Manual Almanac, Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1781

Mahogany, white pine, brass and steel.

ht. 29 in.

Loaned by the Dedham Historical Society and Museum

One of only two known examples with printed tables and dials sold to Willard by the patriot, Paul Revere (1735-1818) as noted in numerous transactions in Revere’s daybook in 1781.

The paper mounted on pine backing attempts to display, day of the week, day of the month, rise and set of the sun and moon, high and low tides, the equation of time, local time in Boston, London, Jerusalem and China, and the Dominical Letter. On this example, it is printed in “vermillion” which was at an added cost.

Eight-day timepiece in the Willard House collection by Aaron Willard (1757-1844), Boston, c. 1835

The mahogany case is painted white, a color called “stone”, and has been incorrectly used as evidence that “white painted” clocks were “bride’s” clocks and given to brides on their wedding day. This nomenclature started in the literature about 100 years ago and continues incorrectly to this day by dealers, collectors and museums. White was one of several colors painted on Willard shelf and wall clocks in addition to bottle green and red. Although rare, white patent timepieces, shelf clocks and furniture forms are known that date well before the “white wedding” of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1840 which began the popularity of brides wearing white at their weddings.

Lower reverse-painted tablet depicting “Mary had a Little Lamb”

New England, mahogany, brass and steel “Wheel-cutting Engine”, circa 1780. This type of “Engine” is well documented in use by clockmaker Daniel Burnap (1759-1838) in Connecticut, and no doubt is the type used by Simon Willard in his Grafton workshop by 1770. The most complicated machine in an 18th century clockmaker’s shop was used to precisely cut the teeth of varying numbers for the various wheels (gears) used in a mechanical clock. First, the number of teeth to be cut was set on the brass index plate below. The slitting saw was then was brought in contact with the brass blank and rotated by hand cutting a slot through the blank. The brass index plate was then rotated for the next tooth, rotating the blank, and the next slot was cut. The basic principles of the process of cutting teeth for a wheel or gear remain to this day, minus the elbow grease!

Detail of the brass index plate showing the rows of concentric numbered index holes for the various numbers of teeth to be cut for the wheels in an 18th century clock. As a tooth slot was cut, the index arm was raised, the brass plate rotated to the next position, thus rotating the blank to be cut a precise distance.

"S Willard's Patent" in 1802 was Simon Willard's (1753-1848) new design of a wall-hanging timepiece. The front of the clock was decorated with the latest French design called "Verre églomisé" or glass gilded and painted on the reverse side. The gold or silver leaf was adhered using a gelatin adhesive, then burnished or etched to provide an almost magical effect when the polished brass pendulum was set in motion behind a mythical depiction of the sun. The gilded and carved rope-molding frame and the gilded pedestal complete the design.